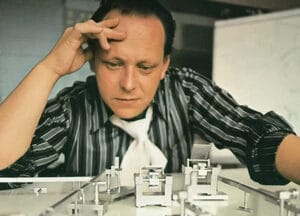

Admittedly, the task is not the easiest: to build easily combinable, high-performance packaging machines for very disparate industries. But perhaps this was the secret to the success of a young visionary from Crailsheim: to see the task not as a simple to-do, but as an exciting tinkering endeavour that is tirelessly driven forward thanks to a wealth of inventive talent. Gerhard Schubert, later Ralf Schubert and, in the third generation, Peter Schubert and their teams developed practical systems that have repeatedly set standards over 60 years. Time for a comprehensive look back.

Packaging machine construction has nothing directly to do with atomic physics. And yet a comparison from this science can help to understand a creative approach that has characterised the industry like no other. Matter consists of protons, neutrons and electrons; the particles form its nucleus - regardless of whether it is an elephant, a glass of water or a car. Schubert packaging lines can be found in various production halls, from pharmaceutical to food manufacturers. And yet the same functional assemblies are always used - pick-and-place stations, case erectors or filling machines. These always consist of the same components, from the machine frame and operator guidance to the robot unit. Those who understand these parts - and offer them as easily combinable systems - may not influence the fate of the material, but they hold the key to the automation of entire industries.

Gerhard Schubert must have had a premonition of this when in 1959 - young, ambitious and employed by Strunck - he told a colleague about the idea of designing packaging machines based on a modular system - a system, mind you, that had yet to be invented. Young age, the spirit of the times or the workload may have been to blame; at Strunck, at any rate, the plan came to nothing. Gerhard Schubert founded his own company in 1966 and pursued the idea with determination, albeit not immediately. In the year the company was founded, he initially developed a carton erector that made a name for itself. After all, it was the first of its kind to work with hot-melt adhesive, i.e. to mould blanks and join them into sturdy boxes in a short space of time. What the patented box erecting and gluing machine, SKA for short, also achieved was that it laid the foundation for a modular system, whether intentional or not; after all, box erectors are one of many components in an assembly group.

From the individual machine to the system

Gerhard Schubert had not forgotten the latter: The successful automation of an important packaging step found its logical continuation just six years later. Schubert reached a milestone with the development of the Schubert modular system for customised machines (SSB), but also reached a crossroads. The modular system signalled a revolution in mechanical engineering, as it enabled manufacturers from different industries to configure highly customised packaging lines from limited assemblies. The foundation stone was laid for what Schubert would later christen the TLM modular system - TLM stands for top-loading machine. There was just one catch:

The purely mechanical design principle of the modular elements allowed for low flexibility - at the expense of efficiency. Classically designed, fixed gripping, sliding or lifting mechanisms work reliably, but reach their limits when formats, product sizes or packaging designs change. Extensive modifications or even new assemblies are then rarely an option. Gerhard Schubert knew that he had to take a completely new direction if the modular system was to have a future.

A glimpse of a successful future followed in the 1970s: During a visit to pharmaceutical manufacturer Johnson & Johnson in Canada, Gerhard Schubert saw how robots automated production lines. What sounds obvious from today's perspective was a novelty at the time: at the time, only the automotive industry was using production robotics on a large scale. To see it in other industries - let alone transfer it to the packaging industry - was almost unheard of. From then on, however, Gerhard Schubert set about developing packaging robots that are still unrivalled today.

Faithful helpers in the packaging process

But why robots, whether for a pharmaceutical or biscuit manufacturer? Especially in markets with frequently changing products and small batch sizes - and there are plenty of these in consumer goods - robot systems offer unbeatable advantages: they are fast, manoeuvrable, compact, recognise which products are in front of them thanks to sophisticated vision systems - and can be reprogrammed using software. No lengthy conversions, no long downtimes. Simply efficient production.

The first Schubert robots had little in common with today's digital high-tech solutions. Nevertheless, they were out of their time: from the 1980s onwards, Gerhard Schubert paved the way for the fully robotised TLM portfolio we know today: Two robots, the SNC-R1, also known as „Roby“, and the SNC-F2, an articulated-arm robot from the very beginning, made it possible to fully automate the packaging of individual products for the first time. Roby made its debut on a chocolate packing line in 1984.

In 1985, the F2 made it possible for the first time to erect, fill and seal cartons with one and the same robot and corresponding tools. As the forerunner of today's F2, the SNC-F2 marked the beginning of a portfolio that would grow considerably over time. Today it also includes the F4, the F3, a number of delta robots and the Transmodul, a transport robot that travels on a space-saving rail system within packaging lines.

Strong team performance

They all come from Crailsheim and the surrounding area. Schubert subsidiaries Schubert Fertigungstechnik in Bartholomä and Schubert System Elektronik in Neuhausen ob Eck contribute important hardware and software. The result: Schubert is the only packaging machine manufacturer to offer robots developed and built in-house in two different kinematics - Scara and Delta. Scara, short for „Selective Compliance Assembly Robot Arm“, simply put refers to „one-armed“ robots. Thanks to their special arm geometry, they offer high rigidity in the vertical direction, but remain flexible in the horizontal plane. As a result, they require little space and have a large radius of action, which is particularly beneficial for wide conveyor belts.

Delta robots such as T3, T4 or T5 have at least three parallel arms that are attached to the top of the frame and connected to a motor; grippers or suction cups are located at the lower end of the arms. Because the triangular arrangement of the arms resembles the Greek letter delta (Δ), the type got its name.

It was a logical progression from this robot family to today's TLM modular system: every module needs a central system component that performs a specific task. And because robots have proven to be excellent at this, they are found in all machines in the TLM modular system. As system components, they form the basis of the modular approach. Incidentally, Schubert once again turned the industry on its head with this approach: before this development, nobody was talking about sub-machines - i.e. independent, fully functional units.

No chain of coincidences

Today, thanks to the innovative strength from Crailsheim, they are standard, as they enable even complex lines to be realised in a pragmatic and time-saving manner: If you combine TLM electrically, pneumatically and mechanically, you build a TLM packaging line. Theoretically, the smallest TLM packaging line could consist of a sub-machine. However, because an isolated pick-and-place station or a single cartoner are of little use on their own, TLM systems consist of an average of 5.5 sub-machines. Large packaging lines have between eleven and 15, with the largest line Schubert has built to date comprising 26.

This is where things really get going: In pick-and-place stations, F4s reach peak performance by picking up products from feed belts at high speed and placing them in trays or boxes, for example. An F3 is an integral part of every carton erecting machine, where it picks up packaging material from magazines - particularly efficiently thanks to its three axes. F2s, which date back to the SNC-F2 from 1984, erect, fill and seal cartons. Delta robots, on the other hand, enable a high robot density: Up to six can work simultaneously in a single TLM frame.

However, nobody should be misled by the division of tasks: Different types of robots can - and must - work together in lines and can be combined as required. This is precisely what makes the flexible system so appealing - and successful - which Schubert has expanded over 60 years to such an extent that it can now be used for almost all pick-and-place and other packaging tasks.

What did his colleagues from 1959 think as they watched their former colleague gradually turn the world of packaging upside down? What is certain is that he was blazing the technologically independent trail that led the fascinating products from Crailsheim into the wider world - and still characterises Schubert today.